Having been in Paris when it hit 42 C was a bit of a shock. Dealing with dramatic heat levels is a necessity to avoid health and other concerns. Tim Schauenberg writes on the Deutsche Welle website about how we can keep them cool. What is your experience?

This entry was originally posted on August 9, 2019 by Rod Janssen, in climate change, urban policies and tagged climate change on the website Energy on Demand.

Cities are heating up. How can we keep them cool?

By 2050, Berlin could be as warm as Canberra in Australia. With cities around the world grappling over solutions to rising temperatures, Germany’s sunniest city is wasting no time to act.

Vineyards in Copenhagen and searing desert-like heat in Rome? That could be a reality in both European capitals by 2050, according to temperature projections for 520 cities worldwide.

“We found that 77% of future cities are very likely to experience a climate that is closer to that of another existing city [in a different bioclimatic region] than to its own current climate,” wrote the scientists from ETH Zurich, a Swiss university for science and technology. The scientists based their calculations on a global temperature increase of 1.5 degree Celsius (2.7 Fahrenheit).

Germany’s capital, Berlin, could see a temperature increase in its warmest months that puts it in line with temperatures currently experienced in the Australian capital, Canberra.

Some in the German city of Karlsruhe are concerned about the trend. Located in the country’s southwest, the city is already one of the warmest and sunniest cities in Germany. The municipality estimates that by 2050 the number of hot days of more than 30 degrees will double to at least 60 days a year.

“There will be more tropical nights when the temperature is around 25 degrees,” said Norbert Hacker, head of the city’s office for environment and worker protection. “Hot nights are almost always worse than hot days because the body doesn’t get a chance to recover. There’s a clear connection between extreme heat and death rates.”

More than 490 people died from the effects of heat in Berlin in the extremely hot summer of 2018. Exact figures for the rest of Europe are unavailable. But if the climate crisis continues unabated, the World Health Organization estimates that by 2050, the global rate for heat-related deaths in elderly people will be 10 times higher than in 1990.

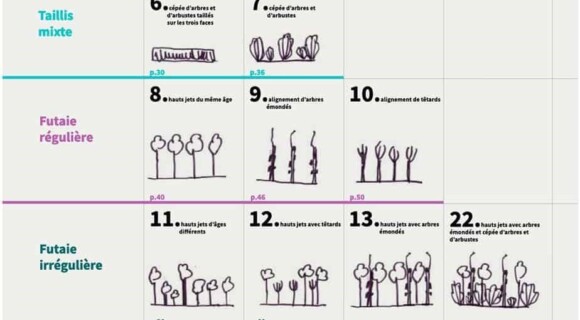

Making the city green

Norbert Hacker’s office is looking at how Karlsruhe’s infrastructure can be changed to adapt to a warming world.

In one neighborhood in the east of the city, “the rooftops of nearly 5,000 citizens have been ‘greened’,” said Klaus Weindel, a landscape architect from the Karlsruhe parks department.

Adding plants to the tops of buildings is an important step, Wendel explained, because it retains precipitation, which brings with it evaporation that helps to keep the city’s climate cool.

Greening building facades is another way to deal with extreme heat. More plants mean better air quality, more shade from the heat on the streets below, and cooler temperatures in the buildings themselves.

Yet Karlsruhe and other cities still have a lot to do if they want to catch up with green leader Singapore. The East Asian metropolis has made 100 hectares of building facades greener and wants to double that figure by 2030. More plant life elsewhere in Karlsruhe could also help, particularly in the sealed interior courtyards of the many old buildings constructed in the mid-19th century, which heat up quickly in hot weather.

Higher temperatures and a persistent drought also mean that the city’s trees are suffering, making them more vulnerable to disease and fungi, with an estimated 20-30% of Karlsruhe’s trees needing to be cut down, according to the local Green Lungs research project.

Karlsruhe is planting “future trees,” including nettle trees and American Ash, that can better deal with warmer weather.

“Trees planted on the edge of the street, are exposed over long periods to temperatures of around 50 C on hot days because of the heat emanating from the asphalt. That makes some of them wilt,” said Andreas Ehmer, who works at the city’s tree nursery. Around a third of the 1,000 new trees planted each year in Karlsruhe are “future trees.”

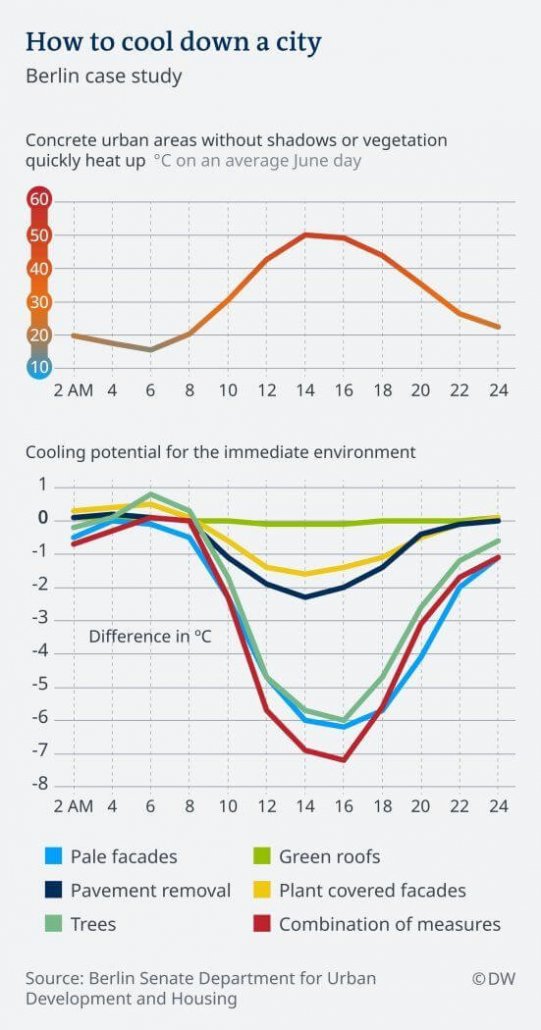

People living in cities can feel the heat even more than those living in rural areas, due to the “urban heat island effect” caused partly by heat trapped in urban concrete and asphalt. Half of the world’s population already lives in cities, most of which are not prepared for rising temperatures.

“The infrastructure in the cities themselves will determine how much of an impact these shifts make,” wrote Emily Clarke, ETH study co-author, in an email to DW.

“Cities tend to be built for very specific climate conditions, and some of the smallest shifts related to average precipitation, temperature, etc. can have a large influence.”

Keeping cool with white walls

Karlsruhe is putting another seemingly minor measure into place that could make a big difference. All public buildings and spaces will be painted in pale colors, and where possible, facades will be plastered white. One NASA report found that a white roof instead of a black one can result in a temperature difference of up to 23 degrees Celsius.

In New York, the Cool Roofs initiative has painted hundreds of thousands of square meters of roofing white, saving 2,282 tons of CO2 a year because the buildings don’t need to use as much energy to cool them down.

Although, an increasing number of German cities are feeling the effects of the climate crisis, fewer than 5% of the country’s municipalities are actually addressing the problem, said Petra Mahrenholz, who heads the center for climate impacts and adaptation at the Federal Environment Agency (UBA). “But many are now aware,” she added.

But is awareness enough? In Karlsruhe, Hacker says there is no special budget for adapting to climate change and he doesn’t see the city introducing it any time soon. The city also has no plans to introduce bigger measures such as creating new green ventilation corridors that allow cool air to flow through the city or transforming streets and parking spots into green areas.

Still, Hacker and his colleagues are working on an action plan for a “heat emergency.” He can, for instance, imagine that urban “cold rooms” might be built to protect people on particularly hot days.

“But that’s not the current state of affairs,” he said. “That could happen if the temperatures continue to rise.” According to the scientists in Zurich, they will.

Images

Documents

No items found

Links

No items found